Kingdom Of Hungary (1526–1867) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Kingdom of Hungary between 1526 and 1867 existed as a state outside the

The Jews of Hungary: History, Culture, Psychology

Wayne State University Press, 1996, p. 153 The Hungarian nobility forced Vienna to admit that Hungary was a special unit of the Habsburg lands and had to be ruled in conformity with its own special laws. However, Hungarian historiography positioned

Royal Hungary (1526–1699), ( hu, Királyi Magyarország, german: Königliches Ungarn), was the name of the portion of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary where the

Royal Hungary (1526–1699), ( hu, Királyi Magyarország, german: Königliches Ungarn), was the name of the portion of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary where the

Conflict and chaos in Eastern Europe

Palgrave Macmillan, 1995, p. 62

As the

As the

Austerlitz, 1805. december 2. A három császár csatája – magyar szemmel

In: Eszmék, forradalmak, háborúk. Vadász Sándor 80 éves, ELTE, Budapest, 2010 p. 557 By the start of the 19th century, the aim of Hungary's agricultural producers had shifted from subsistence farming and small-scale production for local trade to cash-generating, large-scale production for a wider market. Road and waterway improvements cut transportation costs, while urbanization in Austria, Bohemia, and Moravia and the need for supplies for the Napoleonic wars boosted demand for foodstuffs and clothing. Hungary became a major grain and wool exporter. New lands were cleared, and yields rose as farming methods improved. Hungary did not reap the full benefit of the boom, however, because most of the profits went to the magnates, who considered them not as capital for investment but as a means of adding luxury to their lives. As expectations rose, goods such as linen and silverware, once considered luxuries, became necessities. The wealthy magnates had little trouble balancing their earnings and expenditures, but many lesser nobles, fearful of losing their social standing, went into debt to finance their spending.

Napoleon's final defeat brought recession. Grain prices collapsed as demand dropped, and debt ensnared much of Hungary's lesser nobility. Poverty forced many lesser nobles to work to earn a livelihood, and their sons entered education institutions to train for civil service or professional careers. The decline of the lesser nobility continued despite the fact that by 1820 Hungary's exports had surpassed wartime levels. As the number of lesser nobles who earned diplomas increased, the bureaucracy and professions became saturated, leaving a host of disgruntled graduates without jobs. Members of this new intelligentsia quickly became enamored of radical political ideologies emanating from Western Europe and organized themselves to effect changes in Hungary's political system.

Francis rarely called the Diet into session (usually only to request men and supplies for war) without hearing complaints. Economic hardship brought the lesser nobles' discontent to a head by 1825, when Francis finally convoked the Diet after a fourteen-year hiatus. Grievances were voiced, and open calls for reform were made, including demands for less royal interference in the nobles' affairs and for wider use of the Hungarian language.

The first great figure of the reform era came to the fore during the 1825 convocation of the Diet. Count

By the start of the 19th century, the aim of Hungary's agricultural producers had shifted from subsistence farming and small-scale production for local trade to cash-generating, large-scale production for a wider market. Road and waterway improvements cut transportation costs, while urbanization in Austria, Bohemia, and Moravia and the need for supplies for the Napoleonic wars boosted demand for foodstuffs and clothing. Hungary became a major grain and wool exporter. New lands were cleared, and yields rose as farming methods improved. Hungary did not reap the full benefit of the boom, however, because most of the profits went to the magnates, who considered them not as capital for investment but as a means of adding luxury to their lives. As expectations rose, goods such as linen and silverware, once considered luxuries, became necessities. The wealthy magnates had little trouble balancing their earnings and expenditures, but many lesser nobles, fearful of losing their social standing, went into debt to finance their spending.

Napoleon's final defeat brought recession. Grain prices collapsed as demand dropped, and debt ensnared much of Hungary's lesser nobility. Poverty forced many lesser nobles to work to earn a livelihood, and their sons entered education institutions to train for civil service or professional careers. The decline of the lesser nobility continued despite the fact that by 1820 Hungary's exports had surpassed wartime levels. As the number of lesser nobles who earned diplomas increased, the bureaucracy and professions became saturated, leaving a host of disgruntled graduates without jobs. Members of this new intelligentsia quickly became enamored of radical political ideologies emanating from Western Europe and organized themselves to effect changes in Hungary's political system.

Francis rarely called the Diet into session (usually only to request men and supplies for war) without hearing complaints. Economic hardship brought the lesser nobles' discontent to a head by 1825, when Francis finally convoked the Diet after a fourteen-year hiatus. Grievances were voiced, and open calls for reform were made, including demands for less royal interference in the nobles' affairs and for wider use of the Hungarian language.

The first great figure of the reform era came to the fore during the 1825 convocation of the Diet. Count

File:Gróf Széchenyi István.jpg,

After the

After the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

, but part of the lands of the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

that became the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

in 1804. After the Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and thos ...

in 1526, the country was ruled by two crowned kings (John I John I may refer to:

People

* John I (bishop of Jerusalem)

* John Chrysostom (349 – c. 407), Patriarch of Constantinople

* John of Antioch (died 441)

* Pope John I, Pope from 523 to 526

* John I (exarch) (died 615), Exarch of Ravenna

* John I o ...

and Ferdinand I). Initially, the exact territory under Habsburg rule was disputed because both rulers claimed the whole kingdom. This unsettled period lasted until 1570 when John Sigismund Zápolya

John Sigismund Zápolya or Szapolyai ( hu, Szapolyai János Zsigmond; 7 July 1540 – 14 March 1571) was King of Hungary as John II from 1540 to 1551 and from 1556 to 1570, and the first Prince of Transylvania, from 1570 to his death. He was ...

(John II) abdicated as King of Hungary in Emperor Maximilian II

Maximilian II (31 July 1527 – 12 October 1576) was Holy Roman Emperor from 1564 until his death in 1576. A member of the Austrian House of Habsburg, he was crowned King of Bohemia in Prague on 14 May 1562 and elected King of Germany (King ...

's favor.

In the early stages, the lands that were ruled by the Habsburg Hungarian kings were regarded as both the "Kingdom of Hungary" and "Royal Hungary". Royal Hungary was the symbol of the continuity of formal law after the Ottoman occupation, because it could preserve its legal traditions, but in general, it was ''de facto'' a Habsburg province.Raphael PataThe Jews of Hungary: History, Culture, Psychology

Wayne State University Press, 1996, p. 153 The Hungarian nobility forced Vienna to admit that Hungary was a special unit of the Habsburg lands and had to be ruled in conformity with its own special laws. However, Hungarian historiography positioned

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

in a direct continuity with the medieval Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

in pursuance of the advancement of Hungarian interests.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Karlowitz

The Treaty of Karlowitz was signed in Karlowitz, Military Frontier of Archduchy of Austria (present-day Sremski Karlovci, Serbia), on 26 January 1699, concluding the Great Turkish War of 1683–1697 in which the Ottoman Empire was defeated by the ...

, which ended the Great Turkish War

The Great Turkish War (german: Großer Türkenkrieg), also called the Wars of the Holy League ( tr, Kutsal İttifak Savaşları), was a series of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League consisting of the Holy Roman Empire, Pola ...

in 1699, the Ottomans ceded nearly all of Ottoman Hungary

Ottoman Hungary ( hu, Török hódoltság) was the southern and central parts of what had been the Kingdom of Hungary in the late medieval period, which were conquered and ruled by the Ottoman Empire from 1541 to 1699. The Ottoman rule covered ...

. The new territories were united with the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

, and although its powers were mostly formal, a Diet in Pressburg ruled the lands.

Two major Hungarian rebellions were the Rákóczi's War of Independence in the early 18th century and the Hungarian Revolution of 1848

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 or fully Hungarian Civic Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–1849 () was one of many European Revolutions of 1848 and was closely linked to other revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas. Although th ...

and marked important shifts in the evolution of the polity. The kingdom became a dual monarchy in 1867, known as Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

.

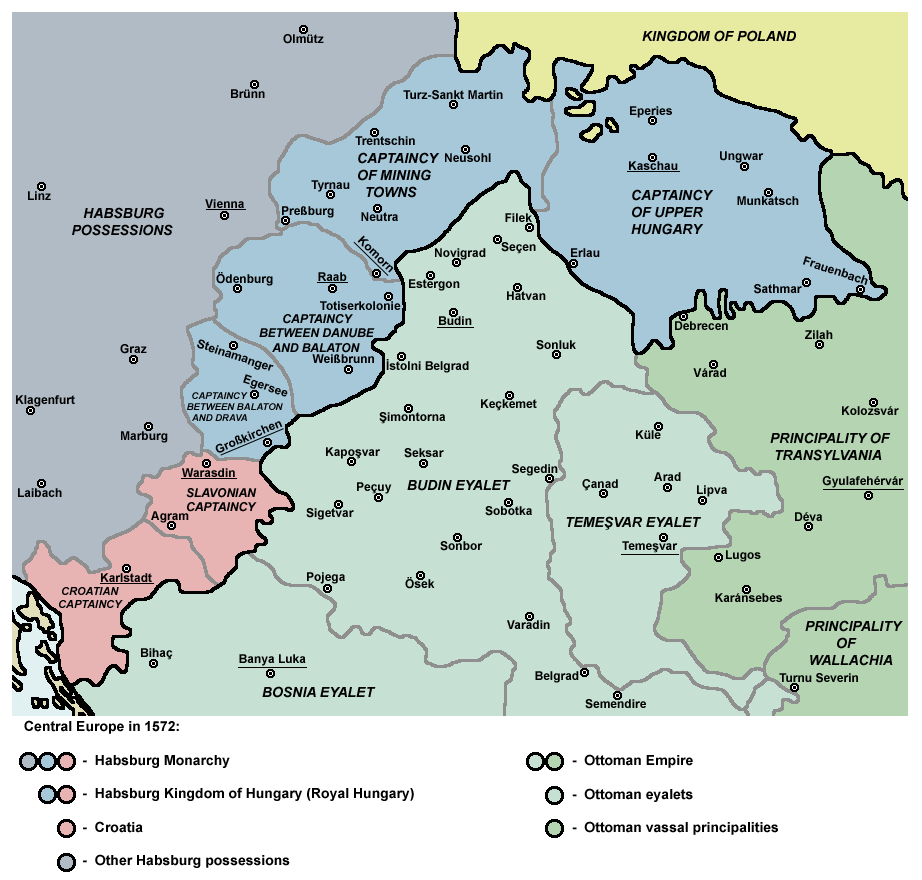

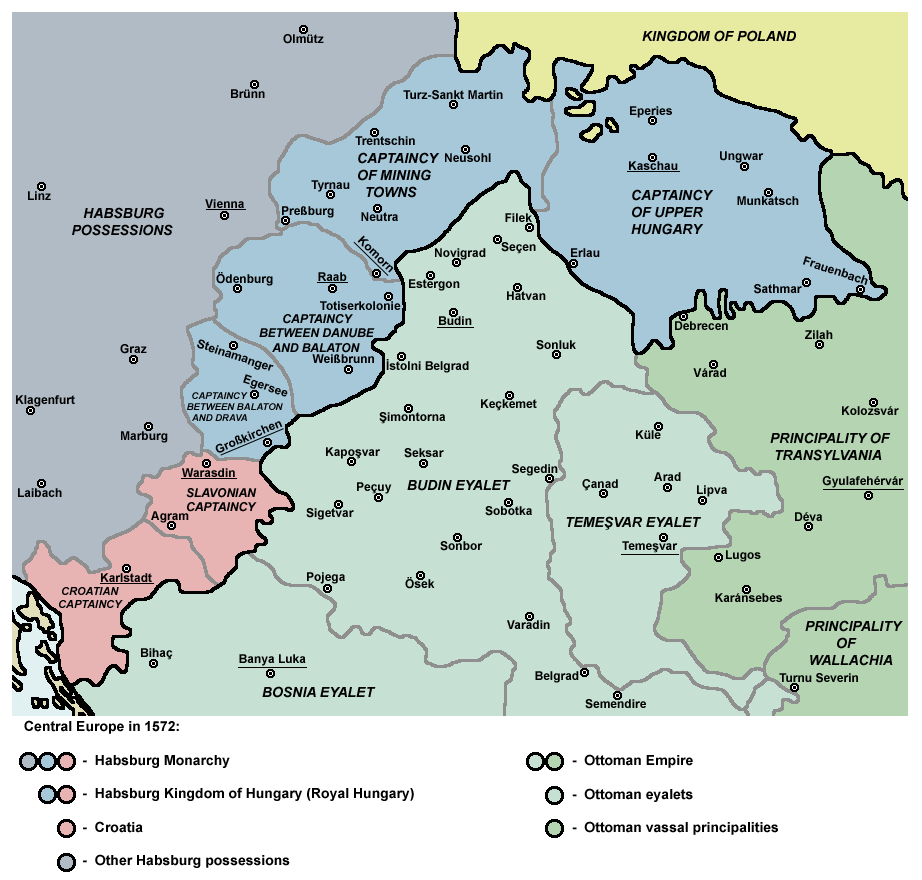

Royal Hungary (1526–1699)

Royal Hungary (1526–1699), ( hu, Királyi Magyarország, german: Königliches Ungarn), was the name of the portion of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary where the

Royal Hungary (1526–1699), ( hu, Királyi Magyarország, german: Königliches Ungarn), was the name of the portion of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary where the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

were recognized as Kings of Hungary

The King of Hungary ( hu, magyar király) was the ruling head of state of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1000 (or 1001) to 1918. The style of title "Apostolic King of Hungary" (''Apostoli Magyar Király'') was endorsed by Pope Clement XIII in 1758 ...

in the wake of the Ottoman victory at the Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and thos ...

(1526) and the subsequent partition of the country.

Temporary territorial division between the rival rulers John I John I may refer to:

People

* John I (bishop of Jerusalem)

* John Chrysostom (349 – c. 407), Patriarch of Constantinople

* John of Antioch (died 441)

* Pope John I, Pope from 523 to 526

* John I (exarch) (died 615), Exarch of Ravenna

* John I o ...

and Ferdinand I occurred only in 1538, under the Treaty of Nagyvárad

The Treaty of Nagyvárad (or Treaty of Grosswardein) was a secret peace agreement between Emperor Ferdinand I and John Szapolyai, rival claimants to the Kingdom of Hungary, signed in Grosswardein / Várad (modern-day Oradea, Romania) on February 2 ...

, when the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

got the northern and western parts of the country (Royal Hungary), with the new capital Pressburg (Pozsony, now Bratislava

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approxim ...

). John I secured the eastern part of the kingdom (known as the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom

The Eastern Hungarian Kingdom ( hu, keleti Magyar Királyság) is a modern term coined by some historians to designate the realm of John Zápolya and his son John Sigismund Zápolya, who contested the claims of the House of Habsburg to rule the ...

). Habsburg monarchs needed the economic power of Hungary for the Ottoman wars. During the Ottoman wars the territory of the former Kingdom of Hungary was reduced by around 70 per cent. Despite these enormous territorial and demographic losses, the smaller and heavily wartorn Royal Hungary remained economically more important than Austria or the Kingdom of Bohemia even by the end of 16th century.

The territory of present-day Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

and northwestern Transdanubia

Transdanubia ( hu, Dunántúl; german: Transdanubien, hr, Prekodunavlje or ', sk, Zadunajsko :sk:Zadunajsko) is a traditional region of Hungary. It is also referred to as Hungarian Pannonia, or Pannonian Hungary.

Administrative divisions Trad ...

were parts of this polity, while control of the region of northeastern Hungary often shifted between Royal Hungary and the Principality of Transylvania. The central territories of the medieval Hungarian kingdom were annexed by the Ottoman Empire for 150 years (see Ottoman Hungary

Ottoman Hungary ( hu, Török hódoltság) was the southern and central parts of what had been the Kingdom of Hungary in the late medieval period, which were conquered and ruled by the Ottoman Empire from 1541 to 1699. The Ottoman rule covered ...

).

In 1570, John Sigismund Zápolya

John Sigismund Zápolya or Szapolyai ( hu, Szapolyai János Zsigmond; 7 July 1540 – 14 March 1571) was King of Hungary as John II from 1540 to 1551 and from 1556 to 1570, and the first Prince of Transylvania, from 1570 to his death. He was ...

abdicated as King of Hungary in Emperor Maximilian II

Maximilian II (31 July 1527 – 12 October 1576) was Holy Roman Emperor from 1564 until his death in 1576. A member of the Austrian House of Habsburg, he was crowned King of Bohemia in Prague on 14 May 1562 and elected King of Germany (King ...

's favor under the terms of the Treaty of Speyer.

The term "Royal Hungary" fell into disuse after 1699, and the Habsburg Kings referred to the newly enlarged country by the more formal term "Kingdom of Hungary".

Habsburg Kings

The Habsburgs, an influential dynasty of theHoly Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

, were elected Kings of Hungary

The King of Hungary ( hu, magyar király) was the ruling head of state of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1000 (or 1001) to 1918. The style of title "Apostolic King of Hungary" (''Apostoli Magyar Király'') was endorsed by Pope Clement XIII in 1758 ...

.

Royal Hungary became a part of the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

and enjoyed little influence in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. The Habsburg King directly controlled Royal Hungary's financial, military, and foreign affairs, and imperial troops guarded its borders. The Habsburgs avoided filling the office of palatine

A palatine or palatinus (in Latin; plural ''palatini''; cf. derivative spellings below) is a high-level official attached to imperial or royal courts in Europe since Roman times.

to prevent the holders amassing too much power. In addition, the so-called Turkish question divided the Habsburgs and the Hungarians: Vienna wanted to maintain peace with the Ottomans; the Hungarians wanted the Ottomans ousted. As the Hungarians recognized the weakness of their position, many became anti-Habsburg. They complained about foreign rule, the behaviour of foreign garrisons, and the Habsburgs' recognition of Turkish sovereignty in Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

( Principality of Transylvania was usually under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, however, it often had dual vassalage -Ottoman Turkish sultans and the Habsburg Hungarian kings- in the 16th and 17th centuries).Dennis P. HupchickConflict and chaos in Eastern Europe

Palgrave Macmillan, 1995, p. 62

Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

, who were persecuted in Royal Hungary, considered the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

a greater menace than the Turks, however.

The Austrian branch of Habsburg monarchs needed the economic power of Hungary for the Ottoman wars. During the Ottoman wars the territory of the former Kingdom of Hungary shrunk by around 70%. Despite these enormous territorial and demographic losses, the smaller, heavily war-torn Royal Hungary had remained economically more important to the Habsburg rulers than Austria or Kingdom of Bohemia even at the end of the 16th century. Out of all his countries, the depleted Kingdom of Hungary was, at that time, Ferdinand's largest source of revenue.

Reformation

The Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

spread quickly, and by the early 17th century hardly any noble families remained Catholic. In Royal Hungary, the majority of the population became Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

by the end of the 16th century.

Archbishop Péter Pázmány

Péter Pázmány de Panasz, S.J. ( hu, panaszi Pázmány Péter, ; la, Petrus Pazmanus; german: Peter Pazman; sk, Peter Pázmaň; 4 October 1570 – 19 March 1637), was a Hungarian Jesuit who was a noted philosopher, theologian, cardina ...

reorganized Royal Hungary's Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and led a Counter-Reformation that reversed the Protestants' gains in Royal Hungary, using persuasion rather than intimidation. The Reformation caused rifts between Catholics, who often sided with the Habsburgs, and Protestants, who developed a strong national identity and became rebels in Austrian eyes. Chasms also developed between the mostly Catholic magnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

s and the mainly Protestant lesser nobles.

Kingdom of Hungary in the early modern period until 1848

18th century

As the

As the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

' control of the Turkish possessions started to increase, the ministers of Leopold I argued that he should rule Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

as conquered territory. At the Diet of "Royal Hungary" in Pressburg, in 1687, the Emperor promised to observe all laws and privileges. Nonetheless, the hereditary succession of the Habsburgs was recognized, and the nobles' right of resistance

The right to resist is a nearly universally acknowledged human right, although its scope and content are controversial. The right to resist, depending on how it is defined, can take the form of civil disobedience or armed resistance against a tyra ...

was abrogated. In 1690 Leopold began redistributing lands freed from the Turks. Protestant nobles and all other Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Urali ...

thought disloyal by the Habsburgs lost their estates, which were given to foreigners. Vienna controlled the foreign affairs, defense, tariffs, and other functions.

The repression of Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

and the land seizures frustrated the Hungarians, and in 1703 a peasant uprising sparked an eight-year rebellion against Habsburg rule. In Transylvania, which became the part of Hungary again at the end of the 17th century (as a province, called "Principality of Transylvania" with the Diet

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

seated at Gyulafehérvár

Alba Iulia (; german: Karlsburg or ''Carlsburg'', formerly ''Weißenburg''; hu, Gyulafehérvár; la, Apulum) is a city that serves as the seat of Alba County in the west-central part of Romania. Located on the Mureș River in the historical ...

), the people united under Francis II Rákóczi

Francis II Rákóczi ( hu, II. Rákóczi Ferenc, ; 27 March 1676 – 8 April 1735) was a Hungarian nobleman and leader of Rákóczi's War of Independence against the Habsburgs in 1703–11 as the prince ( hu, fejedelem) of the Estates Confeder ...

, a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

magnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

. Most of Hungary soon supported Rákóczi, and the Hungarian Diet voted to annul the Habsburgs' right to the throne. Fortunes turned against the Hungarians, however, when the Habsburgs made peace in the West and turned their full force against them. The war ended in 1711, when Count Károlyi, General of the Hungarian Armies agreed to the Treaty of Szatmár

The Treaty of Szatmár (or the Peace of Szatmár) was a peace treaty concluded at Szatmár (present-day Satu Mare, Romania) on 29 April 1711 between the House of Habsburg emperor Charles VI, the Hungarian estates and the Kuruc rebels. It formal ...

. The treaty contained the emperor's agreement to reconvene the Diet in Pressburg and to grant an amnesty for the rebels.

Leopold's successor, King Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to ...

(1711–40), began building a workable relationship with Hungary after the Treaty of Szatmár. Charles asked the approval of Diet for the Pragmatic Sanction

A pragmatic sanction is a sovereign's solemn decree on a matter of primary importance and has the force of fundamental law. In the late history of the Holy Roman Empire, it referred more specifically to an edict issued by the Emperor.

When used ...

, under which the Habsburg monarch was to rule Hungary not as Emperor, but as a King subject to the restraints of Hungary's constitution and laws. He hoped that the Pragmatic Sanction would keep the Habsburg Empire intact if his daughter, Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position ''suo jure'' (in her own right). ...

, succeeded him. The Diet approved the Pragmatic Sanction in 1723, and Hungary thus agreed to become a hereditary monarchy under the Habsburgs for as long as their dynasty existed. In practice, however, Charles and his successors governed almost autocratically, controlling Hungary's foreign affairs, defense, and finance but lacking the power to tax the nobles without their approval.

Charles organized the country under a centralized administration and in 1715 established a standing army under his command, which was entirely funded and manned by the non-noble population. This policy reduced the nobles' military obligation without abrogating their exemption from taxation. Charles also banned conversion to Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

, required civil servants to profess Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, and forbade Protestant students to study abroad.

Maria Theresa (1741–80) faced an immediate challenge from Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

's Frederick II when she became head of the House of Habsburg. In 1741 she appeared before the Diet of Pressburg holding her newborn son and entreated Hungary's nobles to support her. They stood behind her and helped secure her rule. Maria Theresa later took measures to reinforce links with Hungary's magnates. She established special schools to attract Hungarian nobles

The Hungarian nobility consisted of a privileged group of individuals, most of whom owned landed property, in the Kingdom of Hungary. Initially, a diverse body of people were described as Nobility, noblemen, but from the late 12th century ...

to Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

.

Under Charles and Maria Theresa, Hungary experienced further economic decline. Centuries of Ottoman occupation and war had reduced Hungary's population drastically, and large parts of the country's southern half were almost deserted. A labor shortage developed as landowners restored their estates. In response, the Habsburgs began to colonize Hungary with large numbers of peasants from all over Europe, especially Slovaks, Serbs, Croatians, and Germans. Many Jews also immigrated from Vienna and the empire's Polish lands near the end of the 18th century. Hungary's population more than tripled to 8 million between 1720 and 1787. However, only 39 percent of its people were Magyars, who lived mainly in the center of the country.

In the first half of the 18th century, Hungary had an agricultural economy that employed 90 percent of the population. The nobles failed to use fertilizers, roads were poor and rivers blocked, and crude storage methods caused huge losses of grain. Barter had replaced money transactions, and little trade existed between towns and the serfs. After 1760 a labor surplus developed. The serf population grew, pressure on the land increased, and the serfs' standard of living declined. Landowners began making greater demands on new tenants and began violating existing agreements. In response, Maria Theresa issued her Urbarium

An urbarium (german: Urbar, English: ''urbarium'', also ''rental'' or ''rent-roll'', pl, urbarz, sk, urbár, hu, urbárium), is a register of fief ownership and includes the rights and benefits that the fief holder has over his serfs and peasant ...

of 1767 to protect the serfs by restoring their freedom of movement and limiting the corvée

Corvée () is a form of unpaid, forced labour, that is intermittent in nature lasting for limited periods of time: typically for only a certain number of days' work each year.

Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state for the purposes of ...

. Despite her efforts and several periods of strong demand for grain, the situation worsened. Between 1767 and 1848, many serfs left their holdings. Most became landless farmworkers because a lack of industrial development meant few opportunities for work in the towns.

Joseph II

Joseph II (German: Josef Benedikt Anton Michael Adam; English: ''Joseph Benedict Anthony Michael Adam''; 13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg lands from November 29, 1780 unt ...

(1780–90), a dynamic leader strongly influenced by the Enlightenment, shook Hungary from its malaise when he inherited the throne from his mother, Maria Theresa. In the framework of Josephinism

Josephinism was the collective domestic policies of Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor (1765–1790). During the ten years in which Joseph was the sole ruler of the Habsburg monarchy (1780–1790), he attempted to legislate a series of drastic reforms ...

, Joseph sought to centralize control of the empire and to rule it by decree as an enlightened despot

Enlightened absolutism (also called enlightened despotism) refers to the conduct and policies of European absolute monarchs during the 18th and early 19th centuries who were influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment, espousing them to enhanc ...

. He refused to take the Hungarian coronation oath to avoid being constrained by Hungary's constitution. In 1781–82 Joseph issued a Patent of Toleration

The Patent of Toleration (german: Toleranzpatent) was an edict of toleration issued on 13 October 1781 by the Habsburg emperor Joseph II. Part of the Josephinist reforms, the Patent extended religious freedom to non-Catholic Christians livi ...

, followed by an Edict of Tolerance

An edict of toleration is a declaration, made by a government or ruler, and states that members of a given religion will not be persecuted for engaging in their religious practices and traditions. The edict implies tacit acceptance of the religio ...

which granted Protestants and Orthodox Christians full civil rights and Jews freedom of worship. He decreed that German replace Latin as the empire's official language and granted the peasants the freedom to leave their holdings, to marry, and to place their children in trades. Hungary, Slavonia, Croatia, the Military Frontier

The Military Frontier (german: Militärgrenze, sh-Latn, Vojna krajina/Vojna granica, Војна крајина/Војна граница; hu, Katonai határőrvidék; ro, Graniță militară) was a borderland of the Habsburg monarchy and l ...

and Transylvania became a single imperial territory under one administration, called the Kingdom of Hungary or "Lands of the Crown of St. Stephen

The Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen ( hu, a Szent Korona Országai), informally Transleithania (meaning the lands or region "beyond" the Leitha River) were the Hungarian territories of Austria-Hungary, throughout the latter's entire exis ...

". When the Hungarian nobles again refused to waive their exemption from taxation, Joseph banned imports of Hungarian manufactured goods into Austria and began a survey to prepare for the imposition of a general land tax.

Joseph's reforms outraged nobles and clergy of Hungary, and the peasants of the country grew dissatisfied with taxes, conscription, and requisitions of supplies. Hungarians perceived Joseph's language reform as German cultural hegemony

In Marxist philosophy, cultural hegemony is the dominance of a culturally diverse society by the ruling class who manipulate the culture of that society—the beliefs and explanations, perceptions, values, and mores—so that the worldview of t ...

, and they reacted by insisting on the right to use their own tongue. As a result, Hungarian lesser nobles sparked a renaissance of the Hungarian language and culture, and a cult of national dance and costume flourished. The lesser nobles questioned the loyalty of the magnates, of whom less than half were ethnic Hungarians, and even those had become French- and German-speaking courtiers. The Hungarian national reawakening subsequently triggered national revivals among the Slovak, Romanian, Serbian, and Croatian minorities within Hungary and Transylvania, who felt threatened by both German and Hungarian cultural hegemony. These national revivals later blossomed into the nationalist movements of the 19th and 20th centuries that contributed to the empire's ultimate collapse.

Late in his reign, Joseph led a costly, ill-fated campaign against the Turks that weakened his empire. On January 28, 1790, three weeks before his death, the emperor issued a decree cancelling all of his reforms except the Patent of Toleration, peasant reforms, and the abolition of the religious orders.

Joseph's successor, Leopold II (1790–92), re-introduced the bureaucratic technicality which viewed Hungary as a separate country under a Habsburg king. In 1791 the Diet passed Law X, which stressed Hungary's status as an independent kingdom ruled only by a king legally crowned according to Hungarian laws. Law X later became the basis for demands by Hungarian reformers for statehood in the period from 1825 to 1849. New laws again required approval of both the Habsburg king and the Diet, and Latin was restored as the official language. The peasant reforms remained in effect, however, and Protestants remained equal before the law. Leopold died in March 1792 just as the French Revolution was about to degenerate into the Reign of Terror and send shock waves through the royal houses of Europe.

First half of the 19th century

Enlightened absolutism

Enlightened absolutism (also called enlightened despotism) refers to the conduct and policies of European absolute monarchs during the 18th and early 19th centuries who were influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment, espousing them to enhance ...

ended in Hungary under Leopold's successor, Francis II (ruled 1792–1835), who developed an almost abnormal aversion to change, bringing Hungary decades of political stagnation. In 1795 the Hungarian police arrested Ignác Martinovics

Ignác Martinovics ( sh, Ignjat Martinović, Игњат Мартиновић; 20 July 1755 – 20 May 1795) was a Hungarian scholar, chemist, philosopher, writer, secret agent, Freemason and a leader of the Hungarian Jacobin movement. He was ...

and several of the country's leading thinkers for plotting a Jacobin

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = Pa ...

kind of revolution to install a radical democratic, egalitarian political system in Hungary. Thereafter, Francis resolved to extinguish any spark of reform that might ignite a revolution. The execution of the alleged plotters silenced any reform advocates among the nobles, and for about three decades reform ideas remained confined to poetry and philosophy. The magnates, who also feared that the influx of revolutionary ideas might precipitate a popular uprising, became a tool of the crown and seized the chance to further burden the peasants.

In 1804 Francis II, who was also the Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of the other dynastic lands of the Habsburg dynasty, founded the Empire of Austria in which Hungary and all his other dynastic lands were included. In doing so he created a formal overarching structure for the Habsburg Monarchy, that had functioned as a composite monarchy

A composite monarchy (or composite state) is a historical category, introduced by H. G. Koenigsberger in 1975 and popularised by Sir John H. Elliott, that describes early modern states consisting of several countries under one ruler, sometime ...

for about three hundred years before. He himself became Francis I (''Franz I.''), the first Emperor of Austria

The Emperor of Austria (german: Kaiser von Österreich) was the ruler of the Austrian Empire and later the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A hereditary imperial title and office proclaimed in 1804 by Holy Roman Emperor Francis II, a member of the Ho ...

(''Kaiser von Österreich''), ruling from 1804 to 1835, so later he was named the one and only ''Doppelkaiser'' (double emperor) in history. The workings of the overarching structure and the status of the new ''Kaiserthum Kaiserthum, or modern German Kaisertum (), is a German word for Empire in its meaning as a state ruled over by an Emperor, used in the 18th and 19th centuries. It is most known as a description of the Empire of Austria after its creation in 1804.

A ...

''’s component lands at first stayed much as they had been under the composite monarchy that existed before 1804. This was especially demonstrated by the status of the Kingdom of Hungary, whose affairs remained to be administered by its own institutions (King and Diet) as they had been under the composite monarchy, in which it had always been considered a separate Realm. Article X of 1790, which was added to Hungary's constitution during the phase of the composite monarchy uses the Latin phrase "Regnum Independens". In the new situation, therefore, no Imperial institutions were involved in its internal government.József ZacharAusterlitz, 1805. december 2. A három császár csatája – magyar szemmel

In: Eszmék, forradalmak, háborúk. Vadász Sándor 80 éves, ELTE, Budapest, 2010 p. 557

By the start of the 19th century, the aim of Hungary's agricultural producers had shifted from subsistence farming and small-scale production for local trade to cash-generating, large-scale production for a wider market. Road and waterway improvements cut transportation costs, while urbanization in Austria, Bohemia, and Moravia and the need for supplies for the Napoleonic wars boosted demand for foodstuffs and clothing. Hungary became a major grain and wool exporter. New lands were cleared, and yields rose as farming methods improved. Hungary did not reap the full benefit of the boom, however, because most of the profits went to the magnates, who considered them not as capital for investment but as a means of adding luxury to their lives. As expectations rose, goods such as linen and silverware, once considered luxuries, became necessities. The wealthy magnates had little trouble balancing their earnings and expenditures, but many lesser nobles, fearful of losing their social standing, went into debt to finance their spending.

Napoleon's final defeat brought recession. Grain prices collapsed as demand dropped, and debt ensnared much of Hungary's lesser nobility. Poverty forced many lesser nobles to work to earn a livelihood, and their sons entered education institutions to train for civil service or professional careers. The decline of the lesser nobility continued despite the fact that by 1820 Hungary's exports had surpassed wartime levels. As the number of lesser nobles who earned diplomas increased, the bureaucracy and professions became saturated, leaving a host of disgruntled graduates without jobs. Members of this new intelligentsia quickly became enamored of radical political ideologies emanating from Western Europe and organized themselves to effect changes in Hungary's political system.

Francis rarely called the Diet into session (usually only to request men and supplies for war) without hearing complaints. Economic hardship brought the lesser nobles' discontent to a head by 1825, when Francis finally convoked the Diet after a fourteen-year hiatus. Grievances were voiced, and open calls for reform were made, including demands for less royal interference in the nobles' affairs and for wider use of the Hungarian language.

The first great figure of the reform era came to the fore during the 1825 convocation of the Diet. Count

By the start of the 19th century, the aim of Hungary's agricultural producers had shifted from subsistence farming and small-scale production for local trade to cash-generating, large-scale production for a wider market. Road and waterway improvements cut transportation costs, while urbanization in Austria, Bohemia, and Moravia and the need for supplies for the Napoleonic wars boosted demand for foodstuffs and clothing. Hungary became a major grain and wool exporter. New lands were cleared, and yields rose as farming methods improved. Hungary did not reap the full benefit of the boom, however, because most of the profits went to the magnates, who considered them not as capital for investment but as a means of adding luxury to their lives. As expectations rose, goods such as linen and silverware, once considered luxuries, became necessities. The wealthy magnates had little trouble balancing their earnings and expenditures, but many lesser nobles, fearful of losing their social standing, went into debt to finance their spending.

Napoleon's final defeat brought recession. Grain prices collapsed as demand dropped, and debt ensnared much of Hungary's lesser nobility. Poverty forced many lesser nobles to work to earn a livelihood, and their sons entered education institutions to train for civil service or professional careers. The decline of the lesser nobility continued despite the fact that by 1820 Hungary's exports had surpassed wartime levels. As the number of lesser nobles who earned diplomas increased, the bureaucracy and professions became saturated, leaving a host of disgruntled graduates without jobs. Members of this new intelligentsia quickly became enamored of radical political ideologies emanating from Western Europe and organized themselves to effect changes in Hungary's political system.

Francis rarely called the Diet into session (usually only to request men and supplies for war) without hearing complaints. Economic hardship brought the lesser nobles' discontent to a head by 1825, when Francis finally convoked the Diet after a fourteen-year hiatus. Grievances were voiced, and open calls for reform were made, including demands for less royal interference in the nobles' affairs and for wider use of the Hungarian language.

The first great figure of the reform era came to the fore during the 1825 convocation of the Diet. Count István Széchenyi

Count István Széchenyi de Sárvár-Felsővidék ( hu, sárvár-felsővidéki gróf Széchenyi István, ; archaically English: Stephen Széchenyi; 21 September 1791 – 8 April 1860) was a Hungarian politician, political theorist, and wri ...

, a magnate from one of Hungary's most powerful families, shocked the Diet when he delivered the first speech in Hungarian ever uttered in the upper chamber and backed a proposal for the creation of a Hungarian academy of arts and sciences by pledging a year's income to support it. In 1831 angry nobles burned Szechenyi's book Hitel (Credit), in which he argued that the nobles' privileges were both morally indefensible and economically detrimental to the nobles themselves. Szechenyi called for an economic revolution and argued that only the magnates were capable of implementing reforms. Szechenyi favored a strong link with the Habsburg Empire and called for the abolition of entail and serfdom, taxation of landowners, financing of development with foreign capital, the establishment of a national bank, and introduction of wage labor. He inspired such projects as the construction of the suspension bridge linking Buda and Pest. Szechenyi's reform initiatives ultimately failed because they were targeted at the magnates, who were not inclined to support change, and because the pace of his program was too slow to attract disgruntled lesser nobles.

The most popular of Hungary's great reform leaders, Lajos Kossuth

Lajos Kossuth de Udvard et Kossuthfalva (, hu, udvardi és kossuthfalvi Kossuth Lajos, sk, Ľudovít Košút, anglicised as Louis Kossuth; 19 September 1802 – 20 March 1894) was a Hungarian nobleman, lawyer, journalist, poli ...

, addressed passionate calls for change to the lesser nobles. Kossuth was the son of a landless, lesser nobleman of Protestant background. He practiced law with his father before moving to Pest. There he published commentaries on the Diet's activities, which made him popular with young, reform-minded people. Kossuth was imprisoned in 1836 for treason. After his release in 1840, he gained quick notoriety as the editor of a liberal party newspaper. Kossuth argued that only political and economic separation from Austria would improve Hungary's plight. He called for broader parliamentary democracy, rapid industrialization, general taxation, economic expansion through exports, and the abolition of privileges (equality before the law) and serfdom. But Kossuth was also a Hungarian patriotic whose rhetoric provoked the strong resentment of Hungary's minority ethnic groups. Kossuth gained support among liberal lesser nobles, who constituted an opposition minority in the Diet. They sought reforms with increasing success after Francis's death in 1835 and the succession of Ferdinand V (1835–48). In 1844 a law was enacted making Hungarian the country's exclusive official language.

István Széchenyi

Count István Széchenyi de Sárvár-Felsővidék ( hu, sárvár-felsővidéki gróf Széchenyi István, ; archaically English: Stephen Széchenyi; 21 September 1791 – 8 April 1860) was a Hungarian politician, political theorist, and wri ...

, the first great figure of the reform era

File:Flag_of_Hungarian_Revolution_of_1848.png, Revolutionary flag, 1848–49

File:Great coat of arms of Hungary (1849).svg, Arms of Hungary, 1849

File:Kossuth1848.png, Lajos Kossuth

Lajos Kossuth de Udvard et Kossuthfalva (, hu, udvardi és kossuthfalvi Kossuth Lajos, sk, Ľudovít Košút, anglicised as Louis Kossuth; 19 September 1802 – 20 March 1894) was a Hungarian nobleman, lawyer, journalist, poli ...

, the most popular of Hungary's great reform leaders

1848–1867

After the

After the Hungarian Revolution of 1848

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 or fully Hungarian Civic Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–1849 () was one of many European Revolutions of 1848 and was closely linked to other revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas. Although th ...

, the emperor revoked Hungary's constitution and assumed absolute control. Franz Joseph divided the country into four distinct territories: Hungary, Transylvania, Croatia-Slavonia, and Vojvodina. German and Bohemian administrators managed the government, and German became the language of administration and higher education. The non-Magyar minorities of Hungary received little for their support of Austria during the turmoil. A Croat reportedly told a Hungarian: "We received as a reward what the Magyars got as a punishment."

Hungarian public opinion split over the country's relations with Austria. Some Hungarians held out hope for full separation from Austria; others wanted an accommodation with the Habsburgs, provided that they respected Hungary's constitution and laws. Ferenc Deák became the main advocate for accommodation. Deak upheld the legality of the April laws

The April Laws, also called March Laws, were a collection of laws legislated by Lajos Kossuth with the aim of modernizing the Kingdom of Hungary into a Parliamentary system, parliamentary democracy, nation state. The imperative program include ...

and argued that their amendment required the Hungarian Diet's consent. He also held that the dethronement of the Habsburgs was invalid. As long as Austria ruled absolutely, Deak argued, Hungarians should do no more than passively resist illegal demands.

The first crack in Franz Joseph's neo-absolutist rule developed in 1859, when the forces of Sardinia-Piedmont

The Kingdom of Sardinia,The name of the state was originally Latin: , or when the kingdom was still considered to include Corsica. In Italian it is , in French , in Sardinian , and in Piedmontese . also referred to as the Kingdom of Savoy-S ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

defeated Austria at the Battle of Solferino

The Battle of Solferino (referred to in Italy as the Battle of Solferino and San Martino) on 24 June 1859 resulted in the victory of the allied French Army under Napoleon III and Piedmont-Sardinian Army under Victor Emmanuel II (together know ...

. The defeat convinced Franz Joseph that national and social opposition to his government was too strong to be managed by decree from Vienna. Gradually he recognized the necessity of concessions towards Hungary, and Austria and Hungary thus moved towards a compromise.

In 1866 the Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

ns defeated the Austrians, further underscoring the weakness of the Habsburg Empire. Negotiations between the emperor and the Hungarian leaders were intensified and finally resulted in the Compromise of 1867

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 (german: Ausgleich, hu, Kiegyezés) established the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. The Compromise only partially re-established the former pre-1848 sovereignty and status of the Kingdom of Hungary ...

, which created the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary, also known as the Austro-Hungaria

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

n Empire.

Demography

See also

*List of Hungarian rulers

This is a list of Hungarian monarchs, that includes the Grand Prince of the Hungarians, grand princes (895–1000) and the King of Hungary, kings and ruling queens of Hungary (1000–1918).

The Principality of Hungary established 895 or 896, foll ...

Notes

References

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Kingdom of Hungary (1526-1867) .1526 Kingdom of Hungary 1526 Kingdom of Hungary 1526 Kingdom of Hungary 1526 Former countries in Europe Hungary 1526 Kingdom of Hungary 1526 Kingdom of Hungary 1526 Kingdom of Hungary 1526 Kingdom of Hungary 1526 .Kingdom of Hungary .Kingdom of Hungary .Kingdom of Hungary .Kingdom of Hungary 1526 1867 disestablishments in Austria-Hungary Disestablishments in the Kingdom of Hungary (1867–1918) Christian states